You know that surge of focus you get the moment you sit down at your favorite cafe table? You didn't decide to feel it — your brain learned it without you even noticing. That invisible curriculum is called associative learning, and it's running your life more than you think.

At its core, associative learning is the brain's method of linking experiences (according to PubMed research). It can be anything: a sound, a place, or a person that is wired to a feeling or an action. It's the primal form of learning that shapes your routines, your reactions, and honestly, a lot of your so-called "choices" before you even make them. It's not just about Pavlov's dogs; it's about why you crave a snack at 3 pm or feel a spike of anxiety before a meeting.

Understanding this mechanism is the first step to taking the wheel back. The best self-growth starts with knowing how your own mind operates. That's why Headway's library is packed with key insights from psychology and neuroscience in 15-minute summaries you can actually use.

📘 Ready to rewire your patterns? Download Headway and start turning insight into action.

Quick answer: How associative learning works (mechanisms)

Your brain builds connections on the fly, often without your permission. It's a simple, relentless algorithm running in the background: spot what happens together and remember the sequence. The mechanics of this learning process boil down to two core systems. Think of them as your mind's primary wiring methods for associative learning.

1) Linking signal to reaction: Classical conditioning

This part is where your brain learns that one thing predicts another. It's passive and automatic, and here's how it wires up:

A potent, meaningful event (an unconditioned stimulus) causes a hardwired reaction (an unconditioned response). Think of a bitter taste making you gag.

If a neutral, meaningless signal (a neutral stimulus) reliably appears just before that event, your brain starts linking them.

Do it enough times, and the signal works on its own. That formerly blank cue becomes a full-blown conditioned stimulus that can fire off a learned conditioned response all by itself. Even when the bad food is out of the picture, just the sight of its packaging might make your stomach churn. And like that, your brain has stopped waiting for the event. It now reacts to the reliable promise of it.

📘 The key to your habits is associative learning, so apply this skill with Headway.

2) Linking action to сonsequence: Operant сonditioning

This is how you learn from what happens after you do something. Your behavior is active; the consequences teach you:

You try a behavior. The world delivers feedback, also called a consequence.

If the consequence is satisfying or removes something unpleasant, the behavior gets reinforced. In this case, it would be positive reinforcement (adding a reward) or negative reinforcement (removing a burden).

The reinforcement schedules (when and how often a consequence hits) lock the behavior in place. A reward that lands every single time builds a different kind of habit than one that shows up at random. It's the rhythm of payoff that carves the groove.

Beneath it all runs a blunt principle: The law of effect. If it works, do it again. If it backfires, stop. There's no grand philosophy here. It's just your brain's brutally efficient, mostly silent way of sketching a map of what to expect out there, drawing one connection after another.

Classical vs operant conditioning: A side-by-side comparison

Let's cut through the theory: how do these two wiring methods actually differ in your daily life? One shapes your reflexes, and the other directs your actions. Here's the breakdown:

| Aspect | Classical conditioning | Operant conditioning |

|---|---|---|

What's linked | Two external events. A signal and an outcome. | Your own behavior and its result. |

Your role | Passive. Things happen to you. | Active. You do things to the world. |

The outcome | A new trigger for an old reaction. A feeling or a flinch. | A strengthened or weakened habit. A chosen action. |

The pioneer | Ivan Pavlov, known for the bells and salivation. | B.F. Skinner, known for the levers and rewards. |

Real-world wire | Your shoulders tense at your dentist's door. The place recalls past discomfort. | You check your phone when bored. Scrolling has relieved that feeling before. |

Classical conditioning is about prediction. It's your nervous system learning the soundtrack to events. A song tied to a breakup can ache years later. That's Pavlovian conditioning in your emotional circuitry — a conditioned stimulus (the song) pulling a conditioned response (the ache) from thin air.

Operant conditioning lives in the aftermath. It's that loop where your action meets a result. Send a crisp email, get a quick "thanks," and suddenly you're polishing every sentence. That's positive reinforcement doing its job — a core engine of the whole process. The law of effect couldn't be simpler here: whatever works, you'll keep coming back.

One wires your reactions, and the other wires your routines. Together, they form the dual engine of associative learning.

📘 Unlock smarter growth through associative learning and try Headway.

Everyday examples of associative learning

Let's get out of the textbook. Associative learning is the quiet machinery behind your average Tuesday. It's the reason you reach for your phone without thinking, or why a certain song can make you freeze. Here's where the wiring shows:

Your coffee isn't just a drink: You brew it every morning before you sit down to work. After a while, the smell alone — that neutral stimulus — sharpens your focus. Your brain linked the scent to the mental state that follows. Now the smell does the job before the caffeine even hits. That's a conditioned response you built yourself.

Your boss's message tone: It started as a simple chime. Now, when it cuts through the quiet, your breath catches, your shoulders lock. The sound didn't change; its meaning did. Through sheer repetition, it became a conditioned stimulus for alertness, or maybe dread. This response is classical conditioning, writing its rules directly into your nervous system.

Why you take the long way home: You got stuck in a gridlock on Maple Avenue last Tuesday, and the frustration was physical. This Thursday, you signal and turn onto Pine Street without thinking about it. Your brain just calculated: Maple Avenue = trapped, and new route = escape. That's avoidance learning, a blunt form of operant conditioning. You acted to sidestep a remembered ache.

The "good job" that actually worked: Remember when your mentor said two words about your clear formatting? Not a generic compliment, but a specific nod to the work. You noticed you spent extra time on formatting the next project. That's positive reinforcement in the wild. A well-placed consequence made a behavior stick.

The canteen lunch that made you wary: You ate the tuna salad and spent the afternoon sick. Months later, you still avoid that entire section of the menu. That's conditioned taste aversion. Your brain linked the visual stimuli of the container with the physical revolt, forging a single-trial association powerful enough to override logic.

These aren't quirks. They're evidence of a learning process running beneath your choices. Your brain is always correlating, always filing away what precedes what. It builds a map of cause and effect from these tiny events.

The map guides you, often usefully. But sometimes it steers you straight into a rut. Recognizing the landmarks, like the chime, smell, and long way home, is how you start to redraw it.

How associative learning shapes habits and behavior

Here is where theory becomes concrete. Associative learning doesn't just explain reactions; it's the silent contractor that builds and reinforces your daily routines. Your habits are living examples of this learning process, good or bad.

Think of a habit you can't shake. It likely follows a simple, powerful loop: a cue triggers a routine that leads to a reward. That's operant conditioning in practice. But the initial cue? Often, a conditioned stimulus is used in classical conditioning. The ping of a notification (cue) triggers the reach for your phone (routine) for a hit of novelty (reward). Two systems, one automatic behavior.

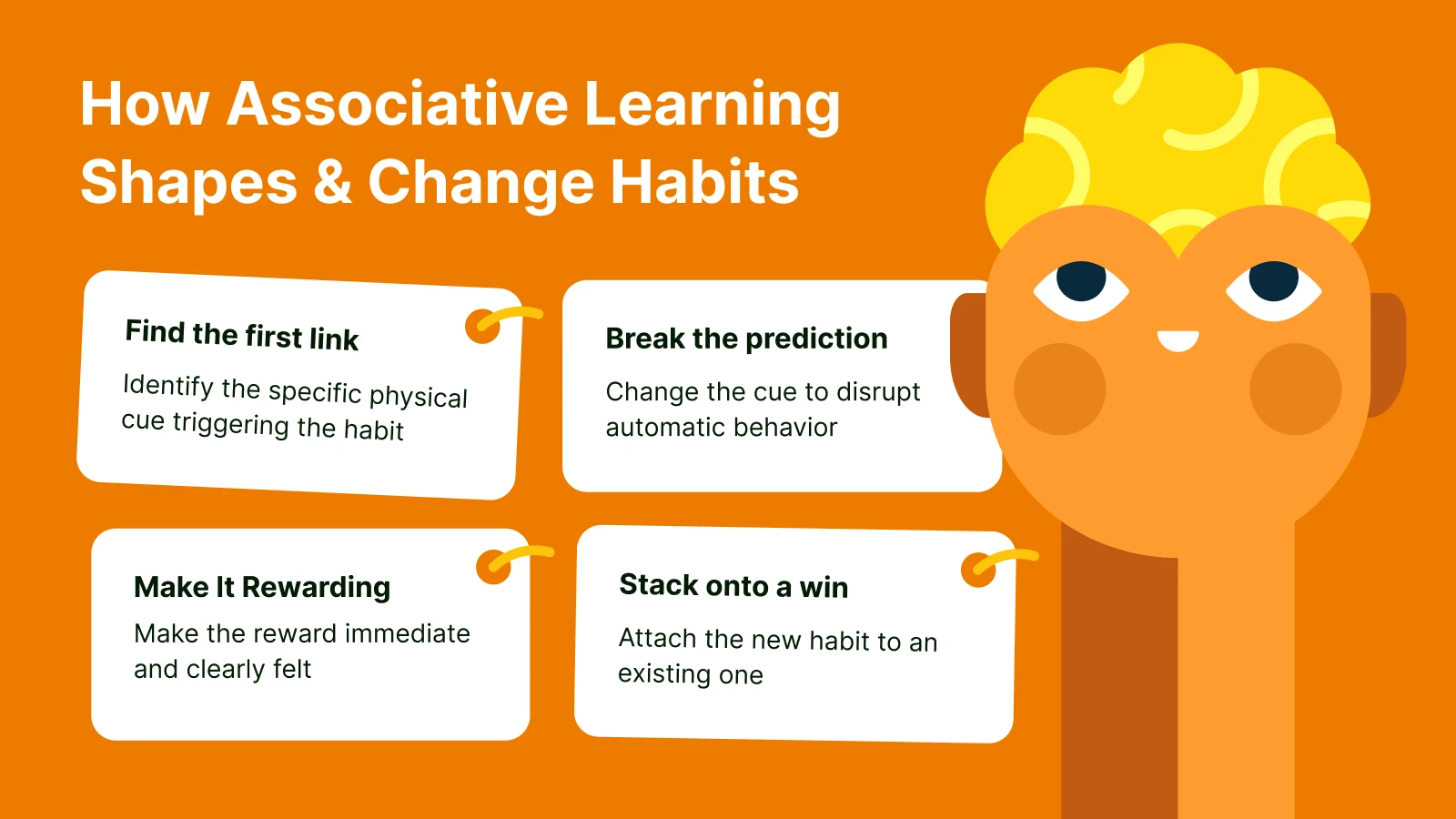

To change a pattern, you don't need more willpower. You need to rewire the associations:

Find the first link: Identify the real, physical cue. Not "I'm bored," but "I'm alone at my desk at 2:30 pm." Be specific, as that trigger is the conditioned stimulus starting the chain.

Break the prediction: Change something, anything, about that cue. Move your phone to another room before you start work. Use a different browser for distractions. You're scrambling the signal so the old behavioral response can't fire on autopilot.

Make the reward undeniable: For a new habit, the payoff must be immediate and felt. Did you write for ten minutes? Immediately stand up and stare out the window at a good view. You are manually applying positive reinforcement, teaching your brain that this action has a worthwhile consequence.

Stack onto a win: Link a tiny piece of a desired new behavior to a habit that's already ironclad. After I pour my morning coffee, before I take the first sip, I will open my notebook. You're grafting new wiring onto an existing, strong circuit.

The goal isn't to out-muscle your impulses, but to understand their architecture. Bad habits are just strong, unhelpful associations. Good ones are useful links, carefully welded. By knowing how the type of associative learning builds your behavior, you stop being its passenger and start drawing the map.

📘 Get Headway — your next breakthrough habit begins with insight!

Modern insights: Neuroscience and applications

The old diagrams from textbooks are now visible in brain scans. Modern neuroscience shows associative learning isn't a metaphor — it's a physical process of wiring and rewiring. At its core is prediction error: your brain forecasts an outcome, and when reality differs, a chemical signal (often dopamine) stamps the new association in. That is the biological law of effect.

Research, visible on PubMed and Google Scholar, maps the circuits. The amygdala ties stimuli to fear. The striatum links actions to rewards. The hippocampus provides the context, solidifying associative memory. Studies published in journals like PLOS ONE (under Open-Access licenses) show that visual stimuli are processed differently during habituation versus sensitization.

This knowledge is applied now. Therapists use it to dissolve phobias by breaking predictive links. Educational tech uses spaced repetition to optimize encoding. App designers use neutral stimulus cues to drive engagement.

Understanding the neuroscience makes it clear: your associations are living pathways in your brain, not life sentences. They were built, and they can be rebuilt.

Don't just read about change – make it happen with Headway!

Understanding associative learning is the starting line. The real work is applying it — rewiring a reaction, rebuilding a habit. That requires more than an article; it needs a clear, ongoing lens on how your mind works.

Headway exists for this: our app gives you the core insights from essential psychology, neuroscience, and microlearning books in 15-minute summaries. It's a direct line to the science behind your patterns — the mechanics of classical conditioning, the leverage points in operant conditioning, and the modern neuroscience of change.

This shift isn't just more information. It's the specific knowledge that lets you edit your own behavior's source code. Stop just reading about how your brain links ideas. Start actively shaping those connections.

📘 Download Headway today and make your next association the one between tapping that link and taking real control of your growth!

Frequently asked questions about associative learning

What is associative learning with an example?

Your brain's main job is spotting what follows what. Smell coffee, feel alert. Hear a boss's message tone, shoulders lock. You didn't choose these links. Your nervous system built them through sheer repetition. One thing starts reliably predicting another, and your reactions rewire. That's it. It's the silent, automatic curriculum running your simplest habits and deepest triggers.

What are the three types of associative learning?

You've got two main engines. Classical conditioning wires a cue to a reflex. Operant conditioning links your action to a payoff or penalty. The third, higher-order conditioning, stacks them: a learned cue itself becomes a new signal. Most real-world behavior — the modal pattern — isn't one type, but several tangled together, building your personal rulebook.

What is the opposite of associative learning?

The opposite is non-associative learning. No links, no predictions. It's just your reaction to one repeated thing changing. A loud fan becomes background noise (habituation). Or a sharp pain makes you flinch harder at a light touch afterward (sensitization). Brain scan research correlates this not with building links, but with dialing single stimuli up or down.

What is an associative learner?

It means your mind works by connection, not logic. You touch a hot stove once. The sight of the coil becomes aversive. You learn avoidance — that's the primary software. An "associative learner" isn't a type of person — it's the condition of having a brain. The goal isn't to stop it, but to see the wiring and become its electrician.